Tendulkar, Ponting and Kallis: When to let go

by The Editor

FEATURE: How do ‘great’ players know when to retire? It’s a tough call. Tougher still for selectors. One helpful tool is to look at a player’s cumulative career average over time. The longer a career (and the greats play for a long time these days), the easier it is to see when one’s form is improving or declining. In the piece below I set out some examples, before looking at Tendulkar, Ponting and Kallis and seeing in what fashion their careers are likely to end.

FEATURE: How do ‘great’ players know when to retire? It’s a tough call. Tougher still for selectors. One helpful tool is to look at a player’s cumulative career average over time. The longer a career (and the greats play for a long time these days), the easier it is to see when one’s form is improving or declining. In the piece below I set out some examples, before looking at Tendulkar, Ponting and Kallis and seeing in what fashion their careers are likely to end.

Tendulkar, Ponting and Kallis: When to let go

By: Gareth van Onselen

Follow @GvanOnselen

Follow @insidecrick

31 July 2012

Introduction

Hanging on too long, when your skill is fading, is a sad way to end a test career. Apart from the obvious – a last public memory that detracts from any previous achievement – it does damage to one’s record and, perhaps more importantly, a team’s chances of success.

When a player is ‘great’ – lauded as a giant of the game – deciding when to end a career is a difficult choice for selectors: keep investing faith in a player’s ability to deliver, based on hope and promise, or make the tough call and drop them, often against public sentiment. The history of cricket is littered with these kinds of decisions and, in each case, they go one way or the other – one bows out at the top of their game or fades away, like a flame gradually starved of oxygen.

The four types of careers

Of course hindsight allows one to see exactly when that turning point is – when in-form becomes out-of-form – it is much more difficult in the moment; nonetheless, it is interesting to see who made the right call, at the right time, and who did not.

Essentially there are four possible ways a career average can go over a long period of time: [1] it can constantly improve throughout a career; [2] it can improve to a certain point then hold steady and level out; [3] it can improve to a certain point, hold steady for a while, then decline gradually; [4] it can improve to a certain point, briefly hold or simply peak, then decline more dramatically over a long period.

Obviously, these trends are relative. We are talking ‘greats’ here, so they will never be too bad and longevity does not lend itself to massive fluctuations and declines.

Some examples

Here are some examples of each type. (Click on a player’s name for full cumulative breakdown)

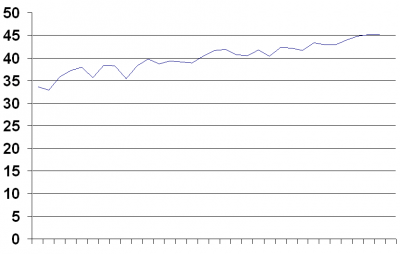

Gary Kirsten is a good example of the first type (and a very rare one at that). Throughout his career his average systematically improved. And his final average of 45, after 101 test matches, was a career high, bar the odd decimal place. Midway through his career, he averaged 40.

Steve Waugh illustrates the the second type. After slowly working his career average up to 50, after 81 tests matches, his average hardly fluctuated a run either side of that for the next 87; finishing with an average of 51.1 after 168 test matches.

Raul Dravid, recently retired, is an example of a subtle decline which represents the third type. His decline was never enough to effect his selection (even when fading he averaged above 50) but noticeable. After working his career average up to an incredible 58.5 after 88 matches, he managed to hold it thereabouts for roughly 20 tests matches, before gradually declining over the last 60-odd, to end with an average of 52.3 after 164 test matches.

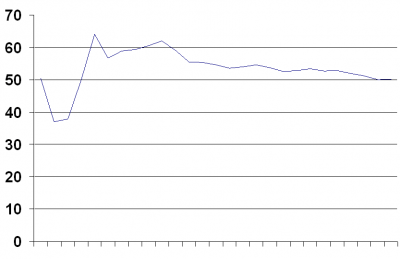

At the other end of the scale, one gets the more extreme and extended decline, perhaps best illustrated by Viv Richards. After 33 matches he had managed to get his average to 60 (even as high as 62), maintaining it at that level for some 10 matches, before a long sustained decline over some 55 test matches (the majority of his career), ending with an average of 50.2 in 121 tests.

Indeed, Richard’s last four series did much damage to his statistical reputation. While he did manage to average 53.7 in this last five-match series against England, the three series that preceded it (12 matches) were the worst run of his career. He averaged less than 30 in each of them, the only time that had happened in his career. Across all four of those final series (17 matches, 24 innings) he averaged 37.5.

So, were we to draw graphs for each of these examples, Kirsten’s would track consistently upwards; Waugh’s would track up then flatline; Dravid’s would represent a very gradual bell curve and Richards’, a more pronounced one. Obviously, if you are a player, you would look to end like Kirsten or Waugh. The third type isn’t too bad, because the decline is so gradual its less noticable or talked about (by the media), but not ideal. Raul Dravid walked a fine line between waiting too long and calling it quits.

Some other modern ‘greats’ – winners and losers

That said, just by way of interest, using a selection recently retired ‘greats’, here are some other examples of the four different types and players and how the point where their average peaked, compares to where it ended. I have included the type in parentheses. In each case the difference is gradual over time, you will have to trust me that there are no wild fluctuations between.

• [3] Adam Gilchrist: 68 matches: 55.7; 96 matches: 47.6

• [4] Herchelle Gibbs: 59 matches: 49.5; 90 matches: 41.9

• [3] Matthew Hayden: 55 matches: 58.1; 103 matches: 50.7

• [2] Justin Langer: 83 matches: 46.6; 105 matches: 45.3

• [2] Sanath Jayasuriya: 27 matches: 49.8; 47 matches; 40.4; 110 matches: 40.1

• [2] Marcus Trescothick: 26 matches: 43.4; 76 matches: 43.8

• [2] Brian Lara: 31 matches: 60.9; 50 matches: 50.7; 131 matches: 52.8

• [1] Stephen Fleming: 11 matches: 34.2; 111 matches: 40.1 (career high)

• [2] Andrew Flintoff: 38 matches: 31.8; 79 matches: 31.8

• [4] Mohammad Yousuf: 73 matches: 56.7; 90 matches: 52.3

You could do the same kind of analysis for bowler’s averages; perhaps an exercise for another day.

One can see that some (Gibbs, Yousuf) let their averages slip away quite dramatically towards the end. Others (like Hayden) had a long gradual decline over time and a large number (Jayasuriya – despite a small mid career peak – and, likewise, Lara) managed to hold their averages steady for the vast majority of their careers, ending off without decline.

This kind of analysis is very telling in a big picture kind of way. Over a long period of time a player’s form and whether it is waxing or waning is unmistakable, the trends are always gradual in one direction or another and, whatever type you look at, I have yet to find an example of a ‘great’ player who achieved some mid-career high, tailed off, and then managed to reverse the trend towards the end of their career.

Tendulkar, Ponting and Kallis

There are three current ‘great’ players (arguably amongst the greatest ever) who, in the next three or four years, will each bring their careers to an end: Sachin Tendulkar, Ricky Ponting and Jacques Kallis.

The obvious question, then, is: if we look at all three of their careers in the same way, what does it tell us about them? Which type is each and, in all likelihood, what does that say about how their career will end?

Let’s have a look (again, click on each player’s name for full cumulative breakdown).

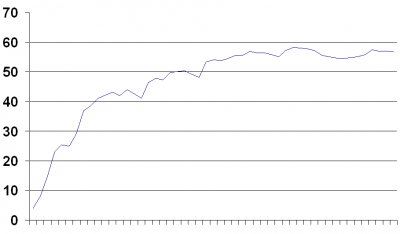

First, Tendulkar. After 29 matches, he had worked his career average up to 50. He then held it thereabouts until his 53 match, when it started to increase again, all the way up to 57.4, in his 83rd match. He held it there (touching 58 at one point) until his 125th test match, at which point it dropped fractionally, down to around 55, where roughly he has been ever since (as things stand, he averages 55.4 after 188 matches). For all intents and purposes, then, a flat line that has lasted around 100 matches, with a margin of around two runs in either direction. As things stand, he is a type two.

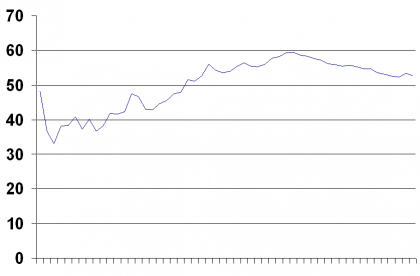

Second, Ponting. Steadily and relentlessly, over the course of 106 matches, Ponting increased his career average to a remarkable high of 59 (peaking at a sublime 59.99). He managed to maintain it in the 59s for 7 innings, before it began to drop. Since his 112th match, through the next 43 matches to the present day, his average has steadily declined. Today, after 165 matches, he sits on 52.7. Whether Ponting manages to level out or continues to dip only time will tell but it would appear he has ruled himself out of the first two category types. Even if it does dip further, so long has his career been and so high is average, you would have to say, at worst, he is a type three. (I said he only touched 59 for 7 innings, but you could take a broader view and say he held his average between 56 and 59 for 40 tests matches).

Third and finally, Kallis. Just like Ponting, Kallis systematically and over the course of 111 test matches increased his average to a remarkable 58. And, for a brief period of a few test matches, it appeared his career would follow the same path as Ponting, as his average had dropped to 54 after 122 tests. But, unlike Ponting, that is were he arrested the decline and he has, since then, systematically increased it, up to where it now sits, after 153 matches, at 57.6. There are, I think, too few runs in it to say for the moment that Kallis is going to be one of those rare players who ends their career with the graph tracking up (remember we gave Tendulkar a four run margin). More likely he will keep at around 56/57 (he first hit an average of 56 after 91 matches, so he has been thereabouts, like Tendulkar, for some 64 tests). But perhaps? If he keeps going like this (he averages 130 for 2012), there is that chance.

It is almost as if he faces the opposite challenge to Ponting. Ponting needs to turn things around or call it a day; Kallis has turned things around and where he ends, well, the next two or three years will tell but that magical mark of 60 must be beckoning.

Postscript

I thought it would be helpful to illustrate the four types graphically. First, Ponting [type 3] and Kallis [type 2]. Here follow their cumulative averages turned into graphs (I did not have the resolve to do Tendulkar too, sorry). For all four graphs, I used the player’s cumulative average at the end of each series they played, rather than every innings, to make the graph more managable, but the effect is much the same.

Here is Kallis’ graph:

You can see that, once he reached around 55, it has stayed there or thereabouts. Now, Ponting:

By contrast, you can see a steady decline from his career high of 59.99. Where will it end?

Next up, type 1, Gary Kirsten. You can see from the graph below that, throughout his career, Kirsten steadily increased his average, finishing at a career high of just over 45:

Finally, type 4 – the steady and dramatic decline, best illustrated by Viv Richards who, over the latter half of his career, saw his average drop by some 12 runs, from 62 all the way down to 50:

To follow Inside Cricket by e-mail simply go to the bottom of the page and fill in your address. When you confirm it, you will receive an e-mail the moment any new post is loaded to the site.

You must be logged in to post a comment.